|

JUXTAPOZ Issue #53, November 2004

Why does YOKO ONO, a world-famous conceptualist Yoko Ono doesn’t paint, yet her paintings changed art history. Her canvas: our minds. Art personified, she evokes allegorical statues of Liberty or Justice, swords in hand, breasts revealed. She appears in Juxtapoz because she challenges highly visual individuals to think beyond their medium, outside the picture frame, to remind them that at the core of every work of art, no matter how complex, lies a simple, definitive idea. Yoko instructs us to imagine an apple, and in our minds an apple appears. She reminds us that sometimes art gets too complicated, outgrowing its own central thesis. On November 9, 1966, John Lennon climbed a ladder at an art opening in London’s Indica Gallery. Suspended from the ceiling, Yoko Ono’s Yes Painting beckoned. Lennon gazed through an attached magnifying glass at a small word upon the large, otherwise-blank canvas. “It’s a great relief when you get to the top of the ladder and you look through the spyglass and it doesn’t say ‘no’ or ‘fuck you,’ it says, ‘yes,’” he later told Jan Wenner in the December ’70 Rolling Stone.

Lennon contemplated Ono’s interactive opus Painting To Hammer A Nail, consisting of nail-studded wood, a hammer hanging from a chain, and a box of nails on a table. Ono, introduced to Lennon by gallery owner John Dunbar, asked the pop star to hammer a nail and hand over five shillings. He responded, “I’ll give you an imaginary five shillings and hammer in an imaginary nail.” John’s surrealistic sense of humor and Yoko’s laconic aloofness suddenly mixed, and clicked. “That’s when we really met,” mused Lennon of that magical moment. From then on Ono dwelt upon the art establishment’s Mt. Olympus, a bigger-than-life character whose conceptual art and music everyone scrutinized. But did you know that prior to marrying a Beatle, Yoko Ono basked in the dim limelight of underground celebrity as a prime mover of the Fluxus art movement, and her 1966 Indica Gallery show, “Unfinished Paintings And Objects,” represented the pinnacle of a brilliant career? Scion of Japan’s premier banking family, Yoko arrived on this planet February 18, 1933. “My mother’s side of the family was very traditional in a sophisticated way. My father’s side was Westernized in many ways.” The Yokohama Bank posted her father, Yeisuke Ono, in San Francisco prior to World War Two, initiating Yoko’s immersion in American culture. She and mom Isoko returned to Japan just before war broke out; the bank reassigned Yeisuke to Hanoi. Despite the Ono family’s ruling-class serenity, they suffered as Japan succumbed to American airpower. On the night of the largest incendiary bombing of Tokyo (March 9, 1945), as a hundred-thousand civilians died, twelve-year-old Yoko crouched in an air-raid shelter. Later evacuated to the country, she almost starved. After the war, the newly-formed Bank of Tokyo hired her dad, and life returned to relative normalcy. Throughout her work, the sky recurs. As a child she saw it as a place of freedom where all could soar. But the sky had rained death on her beautiful land. Such duality informs her art, her music, and her place in the world. “All my life, I enjoyed looking at the sky,” she says. “The sky is constantly changing, the colors are changing, the weather is changing — and that was my security blanket. Even in the middle of the war when the city was all bombed out, the sky was always there.” After the war she went back to school. The first female to study philosophy at Gakushuin University, she got into music, especially opera, creating her instantly-recognizable sonic persona. Her art began to evolve into the cold conceptualism that ultimately leaves the creative grunt-work to the viewer. Yoko, how should your work affect an audience? “Whatever they get is fine. That's all I'm going to get from them anyway.” Returning to America with her parents, she entered Sarah Lawrence College in 1952. The state of art then? “A lot was happening. Artists were different from the general public. There was a Beatnik movement and then gradually the big Hippie movement. Between all that, movements like Fluxus were on such a fringe that it was not really recognized in the big picture, though we felt like we were the center of the world.” How did you feel? “There was struggle and pain trying to be accepted as myself. I was self-abasing in one way and arrogant in another. I was not an easy artist to accept.” Did the self-abasement and arrogance balance out? “I don’t know, I never thought of myself as a balanced person. Basically, I was an obsessed artist. I was obsessive about my beliefs about my work, and I was inspired to create. Going against the stream of things is one of the most organic things an artist does. I was a rebel. It’s an innate part of me to be a rebel.” She left college in 1955, married the pianist Ichiyanagi Toshi, and moved to Manhattan. Yoko set about reducing humanity’s entire aesthetic experience to a few simple commands, which in turn served as the vocabulary for limitless combinations of creation, action, and reaction. She hung out with arty heavyweights such as John Cage, La Monte Young, and Ornette Coleman (with whom she later recorded). Yoko and Toshi staged avant-garde concerts at their loft on Chambers Street. They inhabited a world of Minimalism, Happenings, improvisations, and social upheaval. In November ’61 Yoko performed Piece for Strawberries and Violin at the Carnegie Recital Hall. A Fluxus Movement adherent (“I was there before, during and after Fluxus — ”), she and co-conspirators like George Maciunas, Norman Seaman, Charlotte Moorman and A-Yo reconstructed art’s role in everyday life, following Marcel Duchamp’s wisdom: “Creative art can only be completed by the spectator.” Maciunas’ Fluxus Manifesto proclaimed the need to “…purge the world of bourgeois sickness, intellectual, professional & commercialized culture, purge the world of dead art, imitation artificial art, abstract art, illusionistic art, mathematical art — purge the world of ‘Europanism’ — promote a revolutionary flood and tide in art — promote living art, anti-art, promote non-art reality to be grasped by all peoples, not only critics, dilettantes and professionals…”. Maciunas cited a definition of “flux” as “a flowing or fluid discharge from the bowels or other part, esp. an excessive or morbid discharge.” When her parents learned of her bohemian lifestyle they urged her to return to Japan. Yoko and Toshi moved to Tokyo in 1962. While he lived it up, she stayed home alone; their marriage disintegrated. Depression overwhelmed her. After overdosing on pills, she landed in a mental hospital, held against her will and heavily sedated. Back in New York, Yoko's pal La Monte Young told the musician Anthony Cox about her. Intrigued, Cox flew to Japan, only to find Ono hospitalized. Toshi asked him for help. Cox met with the hospital director, claiming to be an art critic. He threatened to write embarrassing articles about her treatment. Yoko soon got out. Toshi, Tony, and Yoko lived together in Tokyo. When Tony got Yoko pregnant, Toshi filed for divorce. In August 1963, Kyoko Chan Cox was born. Tony returned to New York, then in late ’64 Yoko followed. She and Cox carried on a stormy relationship. Simultaneously, her art career took off. Yoko’s conceptual work from the early 60s, her Fluxus stuff, ranks among the highest art. Succinct, challenging, painfully obvious, it portended a new way of thinking.

No one surpasses her for sheer simplicity of execution. Her graphic text series Instructions for Paintings urges us to take the bull by the horns and conjure in our own heads a given scenario. For example, Painting To See The Skies: Drill two holes into a canvas. Hang it where you can see the sky. (Change the place of the hanging. Try both the front and the rear windows, to see if the skies are different.) — 1961 summer. And Painting to Be Stepped On instructs us to place a canvas on the ground, upon which people will trod. Mend Piece implores us to cut a picture into quarters, put each in a room’s corners, then mentally mend it. Pure idea replaced physical execution. Shifting from objects to concepts while remaining within an objective format, Ono changed art history. At the time, of course, few folks recognized the revolution. In 1964 she published her seminal book Grapefruit, which collected the instructions. Some of Ono’s other “paintings”/installations from the early 60s deserve mention here: Smoke Painting: a canvas smitten with random smoke and fire discoloration as provided by the fiery interactions of viewers; Shadow Painting: a blank canvas positioned so that, as the sun traversed the sky, surrounding objects cast ever-changing shadow patterns; Painting To Let The Evening Light Go Through: a piece of transparent plexiglass through which viewers see the outside world in all its kaleidoscopic complexity; Corner Painting: a canvas cut in half, with the pieces at right angles to each other, designed to hang in a corner. Other notable Ono creations from that era include Sky Machine, a metal-plated postage-stamp dispenser purporting to provide viewers with air; Water Piece (Painting To Be Watered), a self-explanatory array of canvas, sponge, eyedropper, and water vial; Eternal Time, perhaps the pinnacle of conceptual splendor — a clock (with only a minute hand) mounted into a resonating plexiglass box with an attached stethoscope, so that one hears the amplified march of time; Apple, a pedestal crowned by an apple which rots as its exhibition progresses; and of course, Glass Keys To Open The Skies. Yoko, some of the artforms you undertook we now call performance art. “It’s amazing that there’s now a label. There was a confrontational element and a reciprocal element. I asked the audience to directly participate. There was a chance element I couldn’t control. Like the Cut Piece — I’m sitting on a stage, asking the audience to cut a piece of my clothes off me. Anything could’ve happened. I wouldn’t do that now. On stage, I felt I was confronting gods and goddesses within the audience.” During those magical early 60s, Yoko and Tony operated New York’s IsReal Gallery and worked on the film Bottoms, showing hundreds of bare rumps. She displayed an all-white chess set “for playing as long as you can remember where all your pieces are.” Endless socializing with arty intellectuals fueled a frenzy of deconstruction and theorizing. Her next show at Indica Gallery would witness a culmination of her energetic work, and put her on the map. John Lennon admired Yoko Ono’s mirrored sculpture Box of Smile. Peering in to see his reflection, he had to smile. Then he climbed the ladder. The word “yes” triggered an unprecedented coming together. The biggest Anglo pop star ever, he courted an unruly Asian broad who did snooty art nobody understood at the height of the Vietnam War. The scandal-starved public hated her. Beatlemania’s slipstream made her art public property, dissected by pundits, sneered at by rock lunkheads. Never again did Yoko create art in the privacy of her own world. The spotlight always shone, illuminating every idea, every utterance. John and Yoko’s identities morphed into singularity. They appeared on an album cover nude, released unlistenable records, pursued Leftist causes. In response, the Nixon Administration worked tirelessly to deport them as junkies, citing previous busts. Yoko, did you go through the spectrum of drugs? “Oh yes. It was amazing.” Did LSD help your work? “I don’t know. Sometimes it’s a bad trip and sometimes it’s a good trip. In my case, there was no bad trip and it was a longer version of mushrooms. It makes you feel warm and that everything’s alright. These ‘visions’ and this and that — I didn’t go through any of that.” Did smack interfere with your art? “No, strangely enough, it didn’t do that. Acid does. I think on acid, I just had the experience and that’s it. On smack, you can still create things, but I just don’t think it’s necessary.” Yoko became a rock star. With the Plastic Ono Band she and John kicked out hard-ass jams, including gems such as “Money” and “Woman Is The Nigger Of The World” (the cover of Live Peace In Toronto featured, of course, the sky). Unlike the Beatles’ inviting tunes, her music went way beyond the furthest limits of rock raucousness. Screaming operatically to Lennon’s guitar grooves, she imposed her amazing voice upon that captive audience who’d tackle anything the Fab Four threw at them. Yoko, you demanded something out of listeners. “I was into pushing the limits of the form.” Massive John-and-Yoko art projects such as the Bed-In and the Billboards made headlines throughout the 70s. Plastic Ono Band records sold well. Yoko had shows at prestigious galleries. According to art historian Carlo McCormick, “Her unrecognized collaboration with John, beyond the records, was amazing. She came out of Fluxus and performance art, and he came from the greatest stardom, and the mix was really potent. The two best examples are Bed-In and the huge billboard they put up in Times Square, War Is Over. What they did with their fame, no one else could do. Their work still resonates.” She and John had a magically musical kid, Sean, in October 1975. Invariably, we perceive her through the lens of Lennon’s massive presence. Without that enormous exposure, what fame could she have achieved? “Her work has been as consistently misunderstood as her personality has been vilified,” says McCormick. Her graphic and instructional art stayed on course, retaining a simple and majestic style. Her music, however, yielded to Lennon’s gravity, turning her into a crafter of rock tunes rather than a screaming banshee. (Twenty-four years on, one of those tunes, Walking On Thin Ice, remixed, is the number-one dance record in America!) And then, the loss of John’s protective umbra — suddenly, violently and without reason — raises the question: what sort of fucked-up world is this, anyway?

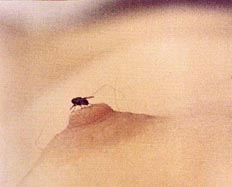

Yoko, how does your visual art relate to your music? “I have no idea. Ask a critic!” Your working routine? “I work whenever and wherever I'm inspired. In the middle of the night, on the plane, or in my dream.” What artists influenced you? “Me.” Describe your continuum of performance art, graphics, photography, and music. “They are all connected, like we are on this planet, and in the universe. It's one big continuum.” Your most satisfying work? “They all gave me the high I needed then. It's like sex. I don't remember which one was a better high.” Tell us about your recent show at Deitch Gallery in New York. “That was very satisfying, like all my works are when they are actually physically realized, I suppose. When the work is still just sitting in my head, it's quite painful. I become impatient for it to be realized.” The show, Odyssey Of A Cockroach, reveals the world from the vantage point of our little beetle buddies. In Yoko’s giant photos we see shoes and legs, garbage-strewn parking lots, and pavement. It puts us in a distressing situation: who wants to be a cockroach? The choice is not ours, but hers. Brilliant! Lightning rod, litmus test, lovely siren of aesthetic finesse, et cetera — Yoko Ono weaves ideas into our brains, and our imaginations explode. |

||||||||||||||||